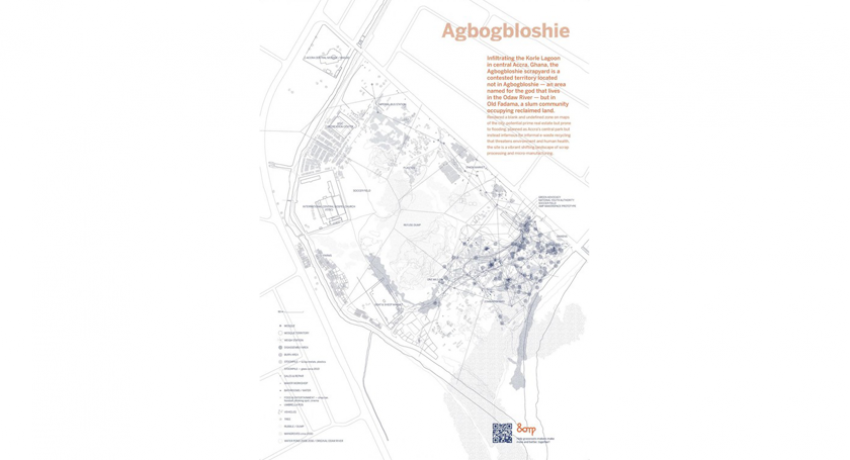

Map of Agbogbloshie created by Osseo-Asare and Abbas for the Seoul Biennale. IMAGE: DK Osseo-Asare and Yasmine Abbas

There is a scrapyard in Accra, Ghana, known as "Agbogbloshie," where e-waste goes to die — at least, that is the way it has been misrepresented and misunderstood by those on the outside. Penn State faculty members DK Osseo-Asare and Yasmine Abbas have spent years working with urban miners — scrap dealers and grassroots makers in and around Agbogbloshie — to tell a more complete story and co-develop strategies for interweaving design innovation into the circular economy of West Africa.

“When you look at Agbogbloshie on a map, it is typically rendered blank, as if nothing happens there … as if nobody wants to see it. We wanted to understand how the scrapyard works — in order to understand its underlying structure and ultimately its urban potential,” said Abbas, assistant professor of architecture in the Stuckeman School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture.

Combining their research interests in digital space and culture, mobility and informal sector urban dynamics, the pair created Agbogbloshie Makerspace Platform (AMP) in 2012 to bring stakeholders together to reimagine the future of Agbogbloshie. Today AMP is bringing positive attention to Agbogbloshie — Osseo-Asare’s TED talk about the scrapyard and its grassroots tech culture published on Aug. 16 already has over a half million views.

While conducting fieldwork in the slum community over multiple years — including interviewing hundreds of scrap dealers to map e-waste processing activities, document the types and throughput of equipment being dismantled, as well as ways of doing business, levels of education, access to tools, technology and life aspirations — Osseo-Asare and Abbas engaged community members, particularly youth, to collaborate with students and recent graduates in STEAM fields (science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics) in a participatory co-design process organized around a series of maker workshops, called AMP qamp (“AMP camps”).

To date more than 1500 youth — approximately 750 from the local community and 750 young STEAM professionals from West Africa, Europe, and the United States — have participated in this co-design process to co-create “AMP Spacecraft,” an alternative architecture for making. Agbogbloshie is a dynamic place not only in terms of how people interact, but also in how it is perceived as a high-energy fluid space activated by the movement of people and materials. The space is designed to support improved making in this context. Osseo-Asare and Abbas describe the space as a “small-scale, mobile, incremental, low-cost and open-source, spacecraft that AMP operates as a set of tools and equipment to 'craft space' in different ways, enabling makers with limited means to jointly navigate and terraform their environment.”

Osseo-Asare, currently a researcher with the Arts and Design Research Incubator, who directs the Humanitarian Materials Lab (HuMatLab) and serves as associate director of Penn State’s Alliance for Education, Science, Engineering and Design with Africa (AESEDA); and Abbas, a grant recipient of the Center for Pedagogy in the Arts and Design in the Penn State College of Arts and Architecture and engineering design faculty in SEDTAPP, are now developing the next phase of the AMP project integrated with their teaching, thanks in part to the support of a College of Arts and Architecture Faculty Research Grant and ongoing efforts of AESEDA to scale the project across West Africa through a network of community-embedded innovation labs.

Because the AMP project is a form of hands-on, real-world design intervention, students from different areas of study are able to get involved in the design and making of a responsive, living wall plug-in and “smart” pollution-sensor canopy for the spacecraft. Noting that the project is part open-source tech-startup, design incubator, and research project all in one, the duo explains that by linking open-source design principles with what they call “stellate design” (a method they have developed for applying design thinking at the urban scale), AMP as a model can help address the needs of the developing world in response to scale and resource constraints. Osseo-Asare and Abbas are explicit about the importance of design as research, rather than thinking of research and design as separate parts of their work.

“What is the role of the University in helping to solve the world’s problems?” asked Osseo-Asare, who has a triple-appointment in humanitarian materials as assistant professor of architecture and engineering design, triangulating the Stuckeman School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, the School of Engineering Design, Technology and Professional Programs (SEDTAPP), and the Materials Research Institute (MRI). “Penn State is doing amazing things, both here in Pennsylvania and around the world. By leveraging our resources and capabilities, we can pioneer technologies that people in the developing world may not. Through open-source tools like software and blueprints, we can support local-global collaboration to solve problems that are bigger than any one of us, but affect us all.”

Makerspaces are redefining what architecture can be, particularly within the context of resource-poor communities that lack more conventional education and training opportunities. Osseo-Asare and Abbas observe that the people in Agbogbloshie are engaging in what is often referred to as “bricolage” or “Jugaad innovation,” doing things themselves and learning from others through improvisational making, part of everyday strategies of survival integrated in the circular economy of the city. Their broader aim is to demonstrate how, by connecting hands-on experience with educational opportunities, more sustainable practices and a better understanding of the innovation potential of places such as Agbogbloshie can emerge.

Osseo-Asare and Abbas strongly believe that fluid spaces of making and improvisation like Agbogbloshie need to exist and should be visible in the city for multiple reasons. On one hand, the people there are doing something important — urban mining — that others do not want (or do not know how) to do. On the other hand, these places operate as platforms that enable temporary anchoring before moving on to “other shores”; they afford new possibilities for urban mobility.

Abbas added, “We need to make recycling radically more sustainable — to protect lives and the environment — which begins with changing mindsets. If we can start to see waste in a better light, recognizing the importance of scrapyards as part of the city’s natural cycle, this gives that space value and we can remake it.”

For more information about AMP, visit https://qamp.net/.

Read the full news story here:

https://news.psu.edu/story/537864/2018/09/21/research/ted-penn-state-and-make...