An international research team, including Penn State faculty Nelson Dzade, reported a new method for creating more durable solar cells that still achieve high efficiency for converting sunlight to electricity. Credit: Provided by Nelson Dzade. All Rights Reserved.

By Matthew Carroll

Next-generation solar materials are cheaper and more sustainable to produce than traditional silicon solar cells, but hurdles remain in making the devices durable enough to withstand real-world conditions. A new technique developed by a team of international scientists could simplify the development of efficient and stable perovskite solar cells, named for their unique crystalline structure that excels at absorbing visible light.

The scientists, including Penn State faculty Nelson Dzade, reported in the journal Nature Energy their new method for creating more durable perovskite solar cells that still achieve a high efficiency of 21.59% conversion of sunlight to electricity.

Perovskites are promising solar technology because the cells can be manufactured at room temperature using less energy than traditional silicon materials, making them more affordable and more sustainable to produce, according to Dzade, assistant professor of energy and mineral engineering in the John and Willie Leone Family Department of Energy and Mineral Engineering and co-author of the study. But the leading candidates used to make these devices, hybrid organic-inorganic metal halides, contain organic components that are susceptible to moisture, oxygen and heat, and exposure to real-world conditions can lead to rapid performance degradation, the scientists said.

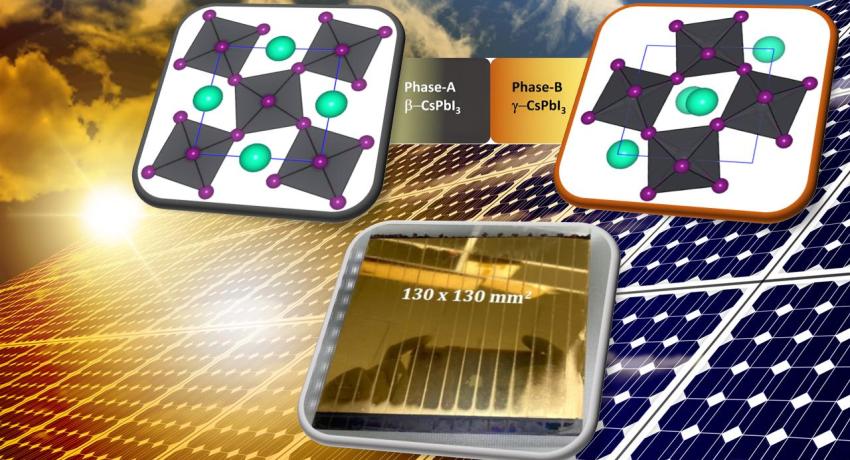

One solution involves turning instead to all-inorganic perovskite materials like cesium lead iodide, which has good electrical properties and a superior tolerance to environmental factors. However, this material is polymorphic, meaning it has multiple phases with different crystalline structures. Two of the photoactive phases are good for solar cells, but they can easily convert to an undesirable non-photoactive phase at room temperature, which introduces defects and degrades the efficiency of the solar cell, the scientists said.

The scientists combined the two photoactive polymorphs of cesium lead iodide to form a phase-heterojunction — which can suppress the transformation to the undesirable phase, the scientists said. Heterojunctions are formed by stacking different semiconductor materials, like layers in a solar cell, with dissimilar optoelectronic properties. These junctions in solar devices can be tailored to help absorb more energy from the sun and convert it into electricity more efficiently.

“The beautiful thing about this work is that it shows the fabrication of phase heterojunction solar cells by utilizing two polymorphs of the same material is the way to go,” Dzade said. “It improves material stability and prevents interconversion between the two phases. The formation of a coherent interface between the two phases allows electrons to flow easily across the device, leading to enhanced power conversion efficiency. That is what we demonstrated in this piece of work.”

The researchers fabricated a device that achieved a 21.59% power conversion efficiency, among the highest reported for this type of approach, and excellent stability. The devices maintained more than 90% of the initial efficiency after 200 hours of storage under ambient conditions, Dzade said.

“When scaled from a laboratory to a real-world solar module, our design exhibited a power conversion efficiency of 18.43% for a solar cell area of more than 7 square inches (18.08 centimeters squared),” Dzade said. “These initial results highlight the potential of our approach for developing ultra-large perovskite solar cell modules and reliably assessing their stability.”

Dzade modeled the structure and electronic properties of the heterojunction at the atomic scale and found that bringing the two photoactive phases together created a stable and coherent interface structure, which promotes efficient charge separation and transfer — desirable properties for achieving high efficiency solar devices.

Dzade’s colleagues at Chonnam University in South Korea developed the unique dual deposition method for fabricating the device — depositing one phase with a hot-air technique and the other with triple-source thermal evaporation. Adding small amounts of molecular and organic additives during the deposition process further improved the electrical properties, efficiency and stability of the device, said Sawanta S. Mali, a research professor at Chonnam University in South Korea and lead author on the paper.

“We believe the dual deposition technique we developed in this work will have important implications for fabricating highly efficient and stable perovskite solar cells moving forward,” said Nelson Dzade, assistant professor of energy and mineral engineering in the John and Willie Leone Family Department of Energy and Mineral Engineering and co-author of the study.

The researchers said the dual deposition technique could pave the way for the development of additional solar cells based on all inorganic perovskites or other halide perovskite compositions. In addition to extending the technique to different compositions, future work will involve making the current phase-heterojunction cells more durable in real-world conditions and scaling them to the size of traditional solar panels, the researchers said.

“With this approach, we believe it should be possible in the near future to shoot the efficiency of this material past 25%,” Dzade said. “And once we do that, commercialization becomes very close.”

Also contributing were Chang Kook Hong, professor, and Jyoti Patil, research professor, at Chonnam National University, South Korea; Yu-Wu Zhong, professor, and Jiang-Yang Shao, researcher, at the Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences; and Sachin Rondiya, assistant professor, Indian Institute of Science.

The National Research Foundation of Korea supported this work. Computer simulations were performed on the Roar Supercomputer in the Institute for Computational and Data Sciences at Penn State.